Using the Kindle DX as a PDF Reader

Lee Hachadoorian on Dec 14th 2011

I was never particularly interested in reading novels on the Kindle, but as an academic I have reams of journal articles—most in PDF format—that I need to read and consult for my research. Many of you will know what I mean when I say that I can’t stand reading on a computer monitor. But printing the articles is problematic, too. There’s the obvious environmental concern, which I partially mitigate by printing everything 4-up double-sided (usually prompting onlookers to ask “Can you read that?!!”), but even then there’s the problem of actually having the articles with you when you find yourself with downtime on the subway, at the doctor’s office, etc. So when my parents asked me what I wanted as a graduation gift…

Which Kindle?

When I got it last May, Amazon had not yet released the Kindle Touch or the Kindle Fire, so my choice was basically between the 6” screen (now renamed Kindle Keyboard) with WiFi (and optionally with 3G wireless) and the 9.7” Kindle DX with 3G wireless only. Obviously, as with laptops, there’s a portability/usability tradeoff. But not knowing how well PDFs would convert to the Amazon e-reader format (read further for notes on PDF conversion), I picked the larger-screen Kindle DX for full-page PDF viewing.

WiFi would have been a nice feature to have. 3G would be great if you want to buy a new book at the beach, but my main need is transferring files that are already on my computer. But the DX was not available with WiFi, and there are still no noises about whether this will happen. Color would be a nice feature to have, and if it were important enough, I could have gone with the Barnes & Noble NOOK Color. But of course the color e-readers, including the new Kindle Fire, don’t use E Ink, which was important to me both for readability and for battery life. Reading on the black & white DX, I can read for a long time without the eye strain that I get when reading on a computer screen. Regarding battery life, the Kindle Fire is supposed to be good for 8 hours of continuous reading. With 3G turned off (which is how I leave it pretty much all the time), my DX gets about a month between between battery charges, and the smaller Kindles are supposed to be good for two months.

The main new feature that I really miss is the touchscreen. The keyboard is horrific for anything longer than a couple of words. Even using it to type in a 2 or 3 digit number—which you have to do to navigate to a particular page—is painful, as it requires hitting the shift key once for each digit in the page number that you want to enter. The navigation buttons are serviceable, but clunky, and I often find myself confusing the Back button and the Previous Page button. Even before the Kindle Touch was announced, comparing the DX to my smartphone, I had already come to the conclusion that this device is begging for a touch screen. In a way, I’m glad that Amazon didn’t release a Kindle DX Touch, because then I really would have regretted buying the DX when I did. But as soon as they add touchscreen and WiFi to the larger screen, I’ll be sorely tempted to upgrade.

Library Management

You can’t read anything until you have content, so the first task, of course, was getting all my PDFs onto the Kindle. Amazon does let you email documents to your Kindle (auto-delivered via 3G or WiFi, depending on the model), but they will charge you 15¢/MB. So my 3 gigabyte library of academic articles would cost me $450 to email to my Kindle. Not bloody likely. Amazon does allow you to email a document to your Amazon registered email address for free, which might seem useless, but you can choose to convert the PDF to the Kindle’s AZW format in the process. You still need to copy the result from your email client to you Kindle.

The most direct way to transfer files is to just plug your Kindle into your computer’s USB port and copy the files over. The Kindle’s storage shows up as an external hard drive. Root level folders include documents, audible (for audiobooks), and system. Anything you copy to the documents folder will show up in your list of “books” on your Kindle. Unless you add the book to a collection, the book will show up on your Home screen (the top-level list that you get to by hitting the Home button). Collections also appear on the Home screen, and if a book is in one or more collections, it will only appear in the collection(s) it is associated with. The Kindle ignores the directory structure, so if you have your files organized in a particular folder hierarchy on your computer, you can copy the entire folder structure to the Kindle’s documents folder, and all those books or articles will show up on your Home screen. The Kindle does not have a traditional file browser, so this hierarchy won’t be represented in any way in the Kindle interface. You might logically assume that the folder a file is in could be its Kindle collection, but collections are more like tags: a book/article can have (be in) any number of collections.

Now you have to keep track of what’s on your hard drive and what’s on your Kindle. Perhaps not so difficult if you’re dealing with dozens of novels, somewhat problematic if you’re dealing with hundreds or even thousands of articles. I ended up using an open source library management software called calibre.

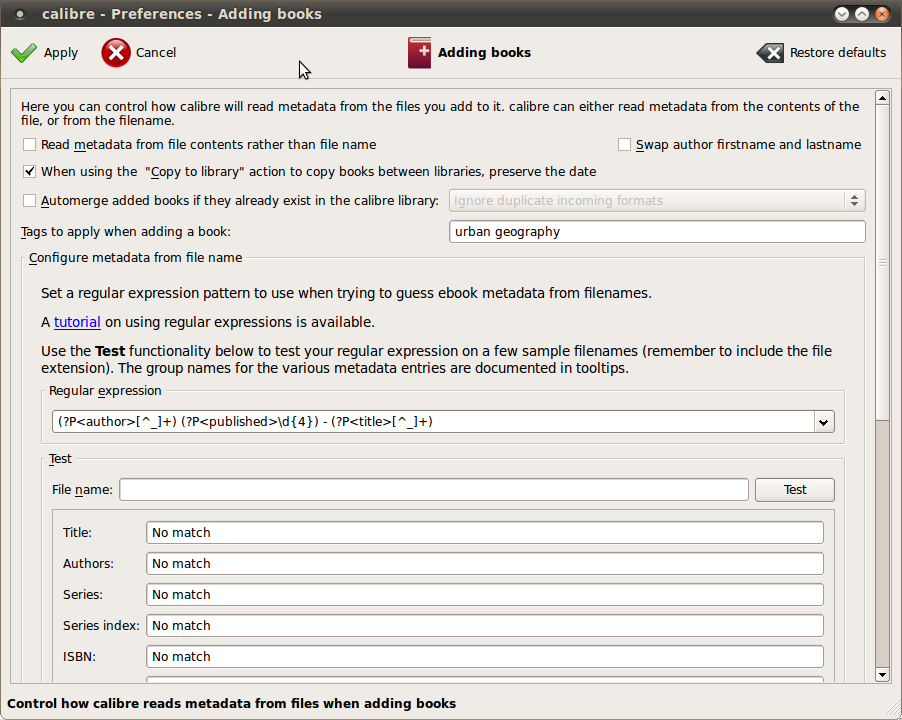

I found it looking for something that could convert PDFs to the Kindle’s AZW format. (It actually converts to MOBI, a format which the Kindle can read, and is in fact exactly the same as the AZW format except for its digital rights management.) It was very easy to direct calibre to import my entire PDF library. Calibre can also create metadata during import, either reading metadata embedded in the PDF, or creating it from the filename. Many of the PDFs in my library lacked metadata, or the PDF “author” was not actually the article author, so the results were quite messy. On the other hand, I usually name the PDFs I download with the author, year, and title, so it was relatively easy to tell calibre what to expect. Calibre relies in several places on regular expressions to parse text. I was able to import a large chunk of my library with the correct author, year, and title using

(?P<author>[^_]+) (?P<published>\d{4}) - (?P<title>[^_]+)

This tells calibre that the metadata comes in three chunks, with the author field (any number of characters) separated by one space from the date field (exactly four digits), separated by space-hyphen-space from the title field (any number of characters). The caret-underscore combination tells the importer to drop underscores, which can be useful as many websites make a practice of using underscores instead of spaces in filenames.

When you connect your Kindle to your computer, calibre detects the Kindle. You can choose to view books/articles on your computer or on your “device” (that is, your e-reader), delete from one or the other, or transfer between them. When browsing the library on your hard drive, a green check mark indicates that the item is also on the connected device. The keyboard shortcut D (for device) pushes the item to the Kindle. Calibre has many other features and many plug-ins, but an absolutely necesary one is the plug-in to manage your Kindle collections. Collections can be created automatically based on tags or database fields (like author name or publisher). This is a godsend because Amazon provides no way to manage Kindle collections other than to type them in on the virtually unusable keyboard and add your books one-by-one. Quite a pain when you’re talking about several hundred articles. And if you have several hundred articles on your Kindle, you have to use collections to keep them organized, or you will spend an awful lot of time scrolling through your articles looking for the one you’re interested in.

In my case, I had my files organized by folder, with each folder being roughly an academic subdiscipline, like urban geography, environmental economics, or political philosophy. Although calibre lets you populate certain fields from filename, it (a) doesn’t let you pull metadata from the path (i.e. folder name), and (b) doesn’t let you write extracted data to tags. But it does let you assign tags to books that you import, as long as you assign the same tags to all the books. So I imported my library to calibre one folder at a time, each time going to Preferences→Adding books and setting “Tags to apply when adding a book:” to the folder name, e.g. urban geography.

Once you have set the tags, you actually need to create the collections on your Kindle. The process is fairly straightforward, but is adequately described elsewhere. One important thing to keep in mind is that once the collections file is pushed to the Kindle, the Kindle needs to be restarted—which is not the same thing as powering it off and on. The regular power off button really puts the Kindle into a sleep mode, and only takes a couple of seconds to turn back on. A full restart is really never needed except for managing collections, but takes a few minutes.

Reading your Articles

As I mentioned, I found calibre looking for a utility to convert my PDFs to the e-reader format. On the whole, PDF conversion was a bust. First, image-based PDFs cannot be converted. Many journals have older articles available as scanned images of the journal pages. Since there is no embedded text, they are essentially image files, and cannot be converted to a text-based format like the MOBI format. (Though if you really want to, Adobe Professional does have built in OCR which could be used to extract the text.)

The next simplest case is text-based PDFs. Here I compared calibre with Amazon’s conversion. Calibre handled the text better. Paragraphs were set off from each other with whitespace, headings were bold and also separated from paragraphs. The Amazon conversion eliminated whitespace between paragraphs, as well as before and after headings. Calibre also forced all fonts to the same size. Amazon preserved relative font sizes. This might seem like an advantage, but this had the effect of pumping up the font size of the body text of most of the document! I think what was happening was that the smallest font size in the document (something from a footnote) was shown using the Kindle’s chosen text size, and everything else was increased relative to that. The overall effect was painfully unreadable. Footnotes are a little problematic. They end up appearing as regular text, as if you read down the page and just kept going from the last line of body text into the footnotes, then continued reading at the top of the next page.

I also converted a short but more complex PDF document with embedded images and tables. The images were mostly bar charts with some explanatory text. With regards to image display, Amazon did a better job. Or rather, the Amazon converter did what it was supposed to do. Calibre did display the images, but as mirror images! Not very useful. Neither converter did a good job with tables. Both of them stacked the columns and printed the result as regular body text (no borders or other formatting), one column after the other. Utterly unusable. If you’ve got anything with tables in it, you pretty much have to leave as a PDF.

Since PDF conversion is time-consuming and the results are at best unattractive and at worst unusable, I decided I was better off leaving PDFs as is. The good news is that the Kindle DX is great for reading native PDFs. The 9.7” diagonal screen size is very close to the page size of many academic journals (The Professional Geographer is 10¾”). In fit-to-screen mode, the Kindle will display the PDF at the maximum possible size while still showing one entire page. Considering that the Kindle PDF viewer automatically trims white space from the edges, many journal articles will display at full size. Even 8½ × 11 PDFs (common for working papers and white papers) are quite readable on the DX, but I also tried reading an 8½ × 11 document on one of the smaller Kindles and found that it was too small to read comfortably on the 6” screen.

If you happen to have journal articles or book chapters scanned as two-page spreads, it would be nice to read these in landscape format. Unfortunately in landscape mode the fit-to-screen viewing option changes to fit-to-width, with unhappy results. The PDF fills the horizontal width of the Kindle screen whether or not it fits vertically, requiring an additional page view to see the bottom of the page, and then an up-and-down to view the second page in the spread, as shown in these images of one two-page spread.

There are alternatives to reading PDFs, even though most academic journal articles are still only available in PDF format. Recently I found out that ScienceDirect (Elsevier) is making their journal articles available in MOBI and ePUB format. I have downloaded and read a few articles this way, and it is excellent. In addition to the standard benefits of using the e-reader format (text reflowing and control over text size), tables of contents, footnotes, and references are hyperlinked correctly. Additionally, even though PDF conversion is rough, calibre does a great job with HTML conversion. While many web pages include various banners and sidebars with navigation links, advertising, blogrolls, etc., many websites (particularly news sites like Chronicle of Higher Education) provide a “Print This” link to show a web page without all the decoration. If you go to a printable web page and save it in the “Web Page, Complete” format, calibre will convert it flawlessly with images in the correct location in the text.

For the Future

One of the features of calibre that I haven’t yet mentioned, and will not go into too much detail about, is it can also download and convert RSS feeds, including blogs and many news websites. This is mostly oriented toward downloading web pages, but since many journals have RSS feeds, I’m currently trying to get this to work with PDFs or even with the e-reader formats on ScienceDirect.

Another issue is that there is a lot of feature overlap between calibre and a reference manager like Mendeley or EndNote, but they’re different enough that you’ll feel that you need both sets of features. No one tool yet has everything I want, and I’m still trying to come up with a work process that get me the benefits of using calibre and a reference manager, without doubling the time I spend managing my library. This might involve keeping a duplicate of the library since calibre is very rigid about maintaining control over its folder hierarchy (unlike Mendeley, which lets you determine the folder hierarchy based on a handful of metadata fields such as journal and author).

If you’re considering buying a Kindle, the tradeoff is between touchscreen and size. Until more academic publishers begin supporting e-reader formats, you’re pretty much stuck with the native PDF format, and the larger Kindle DX is a good call. Hopefully a touchscreen (and WiFi) version of the DX will be released soon.

Filed in Productivity | 2 responses so far

2 Responses to “Using the Kindle DX as a PDF Reader”

[…] blogs we’re exciting this week as well. Lee Hachadoorian over at ‘Free City’ shared his experience using the Kindle DX for PDFs. I’m glad we’re talking about Kindles and eReaders on […]

[…] Commons this past year is, well… hyperlinks galore! I’ve been able to connect to some helpful, important, and inspiring information presented or produced by members of the Commons. More […]